At one point in my life, I was ardently religious. Not some bible-reading crusader, but when thet opic of religion was brought up I was usually the first to speak.

Being young at the time, most of the views I had we're cribbed from my parents and those around me. Being from a rural town, I was hardly aware of viewpoints other than my own being valid at the time.

"Dumb kid" is two words that could definitely be used to describe me.

Some of the people I was friends with back then we're the kind of kids sucked up in a religious fervor that I can't ascribe any positive feelings to.

If you've never had someone tell you you don't believe in 'God' enough to hear his voice you've probably never experienced what I'd like to call the most peculiar feeling in the world.

At a certain point, you'll have enough of it. People didn't give answers, so questions start popping up. In most cases, these questions can't be answered.

The longer questions went unanswered, the more other sources starting popping up.

Maybe it had been my comfort zone at the time, but I checked into other religious faiths.

Nothing ever seemed concrete, the concept of 'faith' was elusive every time I examined it.

What I initially balked at started one of the most peculiar times in my life, especially as a teenager. A person I'm still good friends with asked me if I'd ever heard of Carl Sagan before.

I delved into what little of his writings I could online; for some reason I never went to this library and checked out The Demon Haunted World. Just as that book advertises though, I finally had a candle in the dark. There was no longer a choking cloak of superstition around me; some of the questions I'd had for years suddenly had answers. Anything that wasn't answered, I had a deeper understanding of the set of tools I possessed that I could use to find them.

Remarkably, my desire to learn about the occult didn't really die down. If anything, it was strengthened; it became substantially more fun to approach the subject from an incredibly skeptical viewpoint.

Around the same time a friend had told me about Sagan, I happened to learn about something else that might have had something to do with the way I started viewing religion.

There wasn't actually a whole lot of gaming going on at my house. Being wrapped up in card games, roleplaying and tabletop (among other things) sucked up a huge chunk of my time.

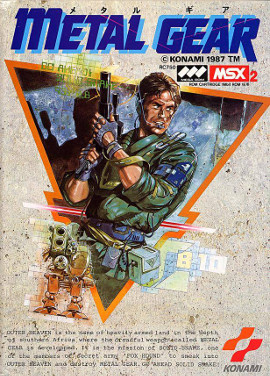

I was busy one day looking around the internet, and stumbled upon Shin Megami Tensei on the SNES. The website that hosted it offered only the barest of description (that website, I believe, was A and TG's Quality Roms) of that game that were more inane 'comedy' bits about the webmasters time spent with it.

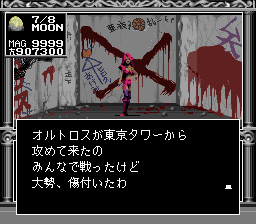

Shin Megami Tensei immediately lept out to me because of it's use of occult and religious symbolism. My previous experience with videogames that did that mainly used it to add spooky flavor to a level or setting; Shin Megami Tensei based its entire concept around theology.

To make a comparison, what I was used to reading about was information backed up by provable fact or testable hypothesis.

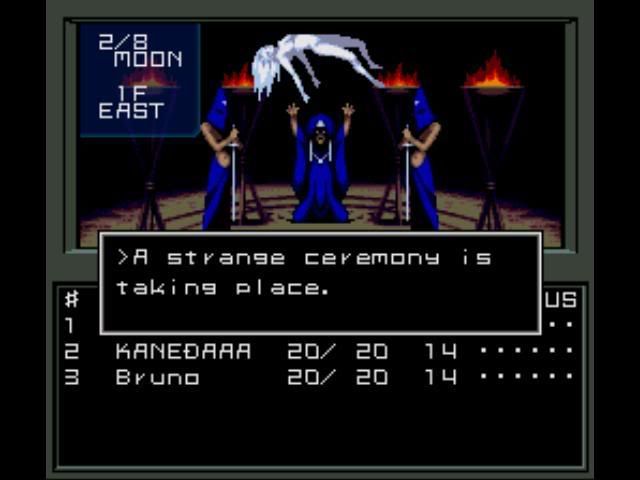

In many ways, SMT is like a videogame version of skeptical theological texts; especially fictional ones. It presents it and the developers views on religion through storytelling and allegory.

Not that I want to imply Carl Sagan and Shin Megami Tensei both are of equal importance; but there's a case to be made that if scientific reasoning can be our 'candle in the dark' perhaps something like Shin Megami Tensei can considered as a painting we can illuminate with those candles.

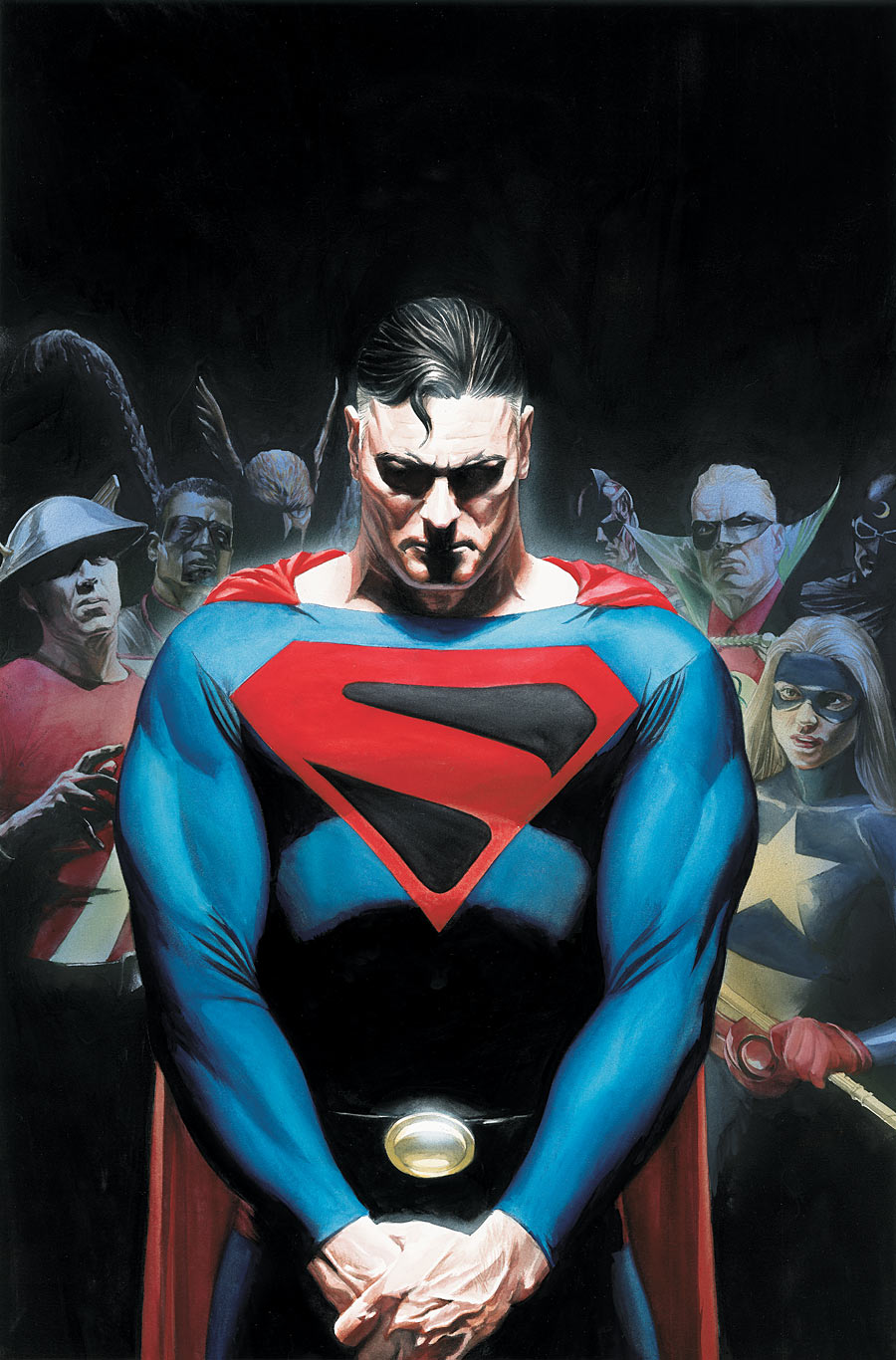

To the effect of that imagery the most, SMT handles it's iconography in a pretty specific way. While it's arguable whether or not the ways it tends to portray that iconography is correct (NSFW)

it's pretty successful when it tries to go out of its way. What that representation is, is the relationship between it's cast's views of religion, and with the occult. Both the sometimes violent xenophobia that religion can cause when bent to the will of malicious people, and the goodwill that people who could be defined as 'truly noble' can accomplish with it are equally represented. Sometimes good isn't neccesarily on the side of Law, and Evil with Chaos.

SMT games tend to open with the protagonist haunted by cryptic visions. Immediately after, the protagonist almost always plays the role of ardent skeptic. I wonder when playing games in the series now if any of the main characters would identify as being atheists during the events of the game. Would a religious man find his faith shaken by the all too often mortal failing of supposed deities?

At a time when I was dealing with a type of rejection form some of my more religious friends, the series dug its claws firmly in me. Sometimes I would notice subtle little critiques of religion; how often the sinister characters we're the ones who only ever accomplished good deeds out of some promised reward in the afterlife.

Sometime around examining characters in videogames, I dumbly realized I could also do it to people I know. Sometimes I would make a shitty mistake like assuming people we're no more nuanced than a simple Law or Chaos hero (or heroine!). Ultimately it had more to do with externalizing my skepticism and critical thinking.

Through what we entertain ourselves with, we can come to understand ourselves.