Comic Books continue to develop and mature as a medium each year.

If not for the talents of an incredibly skilled and diverse group of creators, we could never have reached where we're at right now. Even so, it's kind of been the giant elephant with a spitcurl in the room that for better or worse, Superheroes are here to stay.

To avoid namedropping stuff this early into a Saturday Article, let me just state:

Even today, over 75 years after the dawn of the first Superman comic, there is still a fascination with Superheroes in every part of the world. Japan has its super-popular Henshin heroes, America has the classic icons still present today and everywhere else in the world lends its take on the concept.

Yeah, there are people ardently opposed to the idea of Superhero comics, too. Oddly enough, those sorts of people (especially creators) also help the fascination with Superheroes continue, because they're usually the ones willing to think critically about them first.

What is it, specifically, about the idea of costumed heroes that has then lasted for generations?

When that question was asked in the infancy of Comic Books as a medium, I think the answer might have been a desire to see heroes who were heroic and villains that were evil.

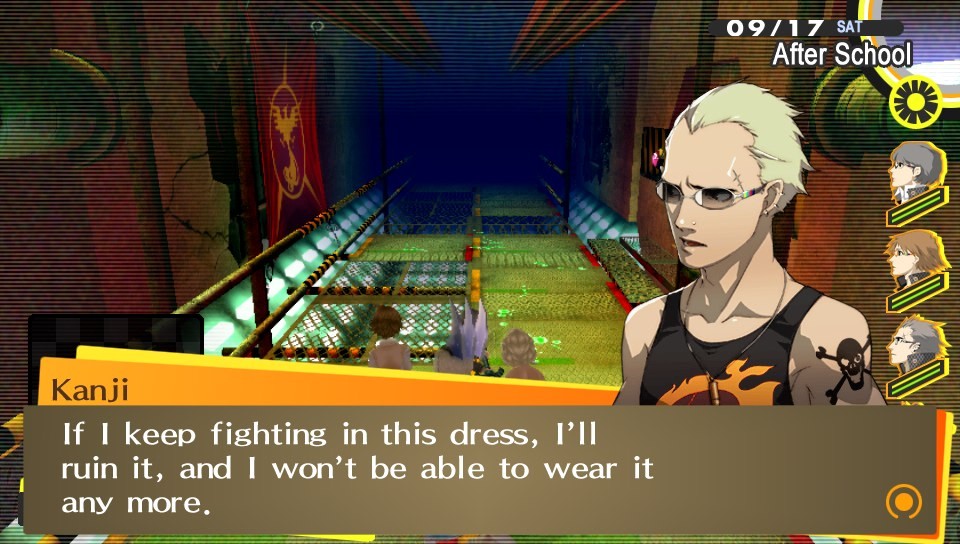

Yet today that answer wouldn't hold up; that kind of black-and-white worldview died around the same time Jason Todd did, end of an age so to speak. We’re in a time now when most Superhero comics – especially creator owned books have started going through some great lengths to make their heroes more fallible and some of their villains more pious and noble.

Batman is the good guy and The Joker is the badguy. We know that by way of how both characters operate in relation to each other. In earlier comics, that relationship had commonly been enough.

The question that writers are willing to pose now are things like whether or not a hero creates his own circumstances, his own villains. Could the continued existence of one or the other even be considered a good thing for Gotham City?

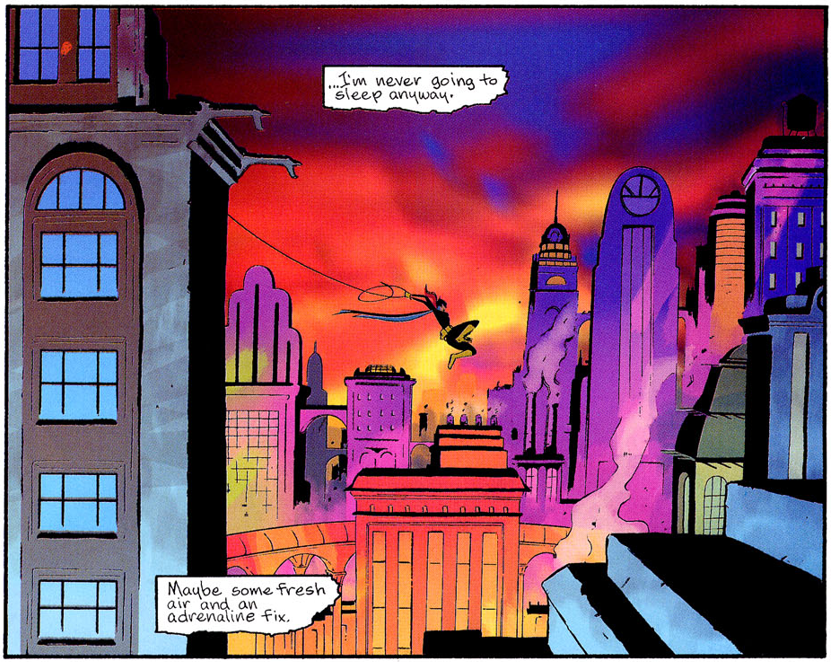

More common, creators are starting to examine what the effect of people with superpowers existing in the ‘real world’ actually might be. Works like this can be placed all over the scale of cynicism versus optimism. That concept is also fairly new - outside of outright parody or pastiche, it wasn't something that commonly came up in Silver and Golden Age comics.

As we've allowed our heroes to age, we're more willing to question them and question what they represent. Just as some characters hold up poorly to scrutiny, some are just as strong as others; a testament to the strength of the Superhero in the minds of pop culture aficionados.

While they've in turn aged and yet stayed eternally young (besides some Elseworlds stories!)

The concept has changed as the same happened to the world and our culture.

At this point, it doesn't really matter what kind of perosn you are, there’s probably a story about folks in tights punching each other that suits your personality and worldview.

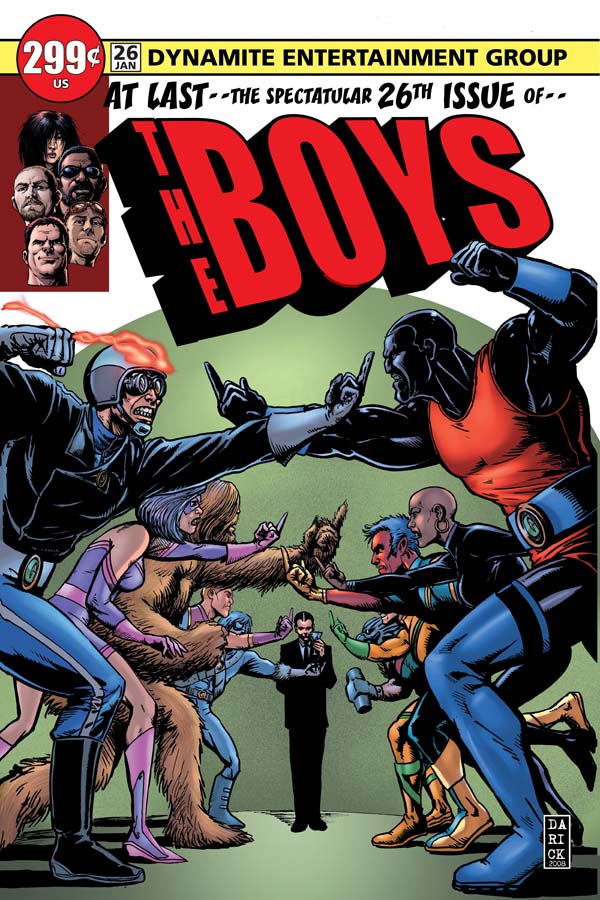

Some people take to The Boys as if it were the only valid critique of Superheroes, depicting them all as deranged and sex crazed psychopaths above the law. Other people might see The Watchmen as the sort of ur-example of a Superhero deconstruction, so powerful that it's tone affected comics for almost twenty years after its release.

On the opposite end towards the optimistic side, you have people willing to accept that

a story like Kurt Busiek's Astro City or All-Star Superman can not only exist in the same market that spawned The Boys but that all of those takes on the concept might be just as valid as the others.

Superheroes have now been around almost as long as the, if nothing else, admirable works of J.R.R. Tolkien and have decidedly the same cultural impact. People are as used to the concept

of Superheroes as they are the kind of journey and mythology that Tolkien created in The Hobbit.

Perhaps our costumed crimefighters are even stronger still than the works of Western Epic Fantasy.

See - might main problem with J.R.R. Tolkien is that every work that followed was beholden to the 'rules' he laid out. Sure, some stories have gone in different directions but the most popular examples and what most people tout as inspiration always follow that groundwork he laid out.

Superhero stories aren't set to anything resembling that, people are as used to the concept now as any of the worlds in Tolkiens writings. When a creator wants to do something new with that, they don't have to waste time introducing or explaining things that people already understand.

The reason for that strength - and another reason for our fascination might be the absense of any particular Superhero 'canon'. It's not just understood - it's accepted that not all Superhero stories are going to follow a mythos similar to Superman or any other existing characters.

When your cultural icon is as easy to identify and understand as Superman is, anyone is free to put their own spin on things.

I'd never discount the his contributions to the medium, but even Alan Moore is a quite famous detractor of the Superhero. Very recently he was quoted as essentially saying the genre is for emotionally stunted adults, but he's also not reading any of the genre-comics that have been released in the last decade.

So even when old-wizard-grandpa Alan Moore says it, I can't agree with it. Dozens of other writers have sense weighed in on his quote, some of them even agreed. My take away from it isn't so much about the statement, but more of what it implies. Even negatively, Alan Moore is still fascinated with Superheroes as a concept. I don't doubt for a minute he wants to know how they continue to persist even though by all rights pop-culture should have outgrown them decades ago.

|

| Kamala Khan |

Maybe it's because a Superhero can be anyone - no one is told they can't be a Superhero based on the color of their skin, their religion, their gender identity or anything else. Comics now are becoming more diverse every year and it's a very welcome change. Just like anyone can be a Superhero, so can any story be written as a Superhero story.

This is a bit of a double edged sword. Even as strong as the concept is, it's led to a lot of alternate stories getting pushed out of the comic market before they could really make their mark.

Writers like Alan Moore are disgruntled and continue to stew about it not because the medium itself, but how the industry has affected that medium. Fortunately, alternate publishing companies are starting to spring up almost every week, offering a wider variety of titles than there ever has been.

In other words, there’s starting to be competition. Writers, artists, readers have finally discovered that while Superheroes aren’t going anywhere anytime soon, other types of stories can be supported strongly by the medium.

Some of the most popular comics in recent years have had nothing to do with bastions of truth, justice and the American way and that’s an absolutely fantastic thing.

When the medium is allowed to grow more, like fiction and film before it, the stories people create with Comic Books can only in turn become more complex.

Recently, there’s even been a trend of ‘the big two’ (Marvel/DC) to branch out their types of stories more. I’ve been on a bit of a Matt Fraction kick lately so I’ll go ahead and mention that he’s one of the most notable creators for doing publisher-owned books as well as independent comics.

While he wrote Hawkeye, which itself is incredibly notable for having a massive effect on comics lately, he's also a bit of an independent comic giant.

His comic Casanova is a good example of comics being able to tell spectacular adventure stories that aren’t about Superheroes. If you haven’t read it, Casanova plays out like some sort of intergalactic James Bond story only if the author was inspired by psychedelics.

Matt Fraction had tied the book closer to spy fiction stories like The Man From U.N.C.L.E. and sci-fi from the 60’s and 70’s than he did Superheroes, while still managing to fill the book with larger than life characters and events.

Yet those very same tropes and elements Matt Fraction uses in Casanova have also been sort of co-opted by Superhero comics as well. Marvel has their ubiquitous super-spy organization S.H.I.E.L.D. which has itself recently become the subject of a TV series. DC has Cadmus and Checkmate and dozens of these, all borrowing elements from popular spy fiction and espionage tales that were written in the last several decades.

DC has even been willing to take it further lately with the announcement that one of their most popular characters, Dick Grayson (Nightwing/The original Robin) is going to be going all shaken-not-stirred on readers when he goes from Superhero to Super-Spy in his new series.

Superheroes have maintained for the last seventy-five years in part to their ability to permeate almost all avenues of not only genre fiction, but the entirety of fiction itself.

Different authors have been giving us new takes on the same established concepts for years, each other twisting it or looking at it from a wholly separate angle than the ones before.

Just like a comic fan might prefer one book over the other, so too is each creators take on the concept just as valid as any other.

There’s no established Superhero ‘canon’ between companies on what makes an acceptable story like with what people expect from something like Epic Fantasy.

As an example, J.R.R. Tolkien wrote The Hobbit in the thirties, in a way it’s a contemporary work of the Siegel and Shusters earliest Superman comics.

Yet despite the time frame they’ve both been allowed with, The Hobbit almost codified the entire genre of Western Fantasy. When someone picks up a book with the most lointclothed and armored motherfucker on the cover with a sword above his head and maybe the grimmest title they’ve ever heard of plastered across it, they still expect a formula similar to The Hobbit just from the title alone.

Being able to defy the readers expectations; that right there is what I think the fascination with Superheroes is really all about. That the next time I pick up a new series, it could be absolutely perfect and tailored specifically to me; or that it could use devices I am familiar with to set up something new or deconstruct what already exists.

This isn’t about individual characters or adventures, but how Superhero comics – and if you were to look at it, the medium entirely, is participated At some point writers start thinking they know and understand what the genre can offer, once things start becoming stale and old someone who’s unafraid of deconstructing things comes along.

Sure, Superhero comics could be juvenile; in some cases they are. That doesn’t mean that there’s not a better future for the genre waiting for the day it can break out of juvenile fascination and the tired boys club mentality that’s seemingly grasped hold of the entire industry.

We’re fascinated by Superheroes, because as our society changes, so do they.